Welcome to the David J. Hindlemann World War II Archive

This tribute page shares stories and images covering David’s service.

This tribute page shares stories and images covering David’s service.

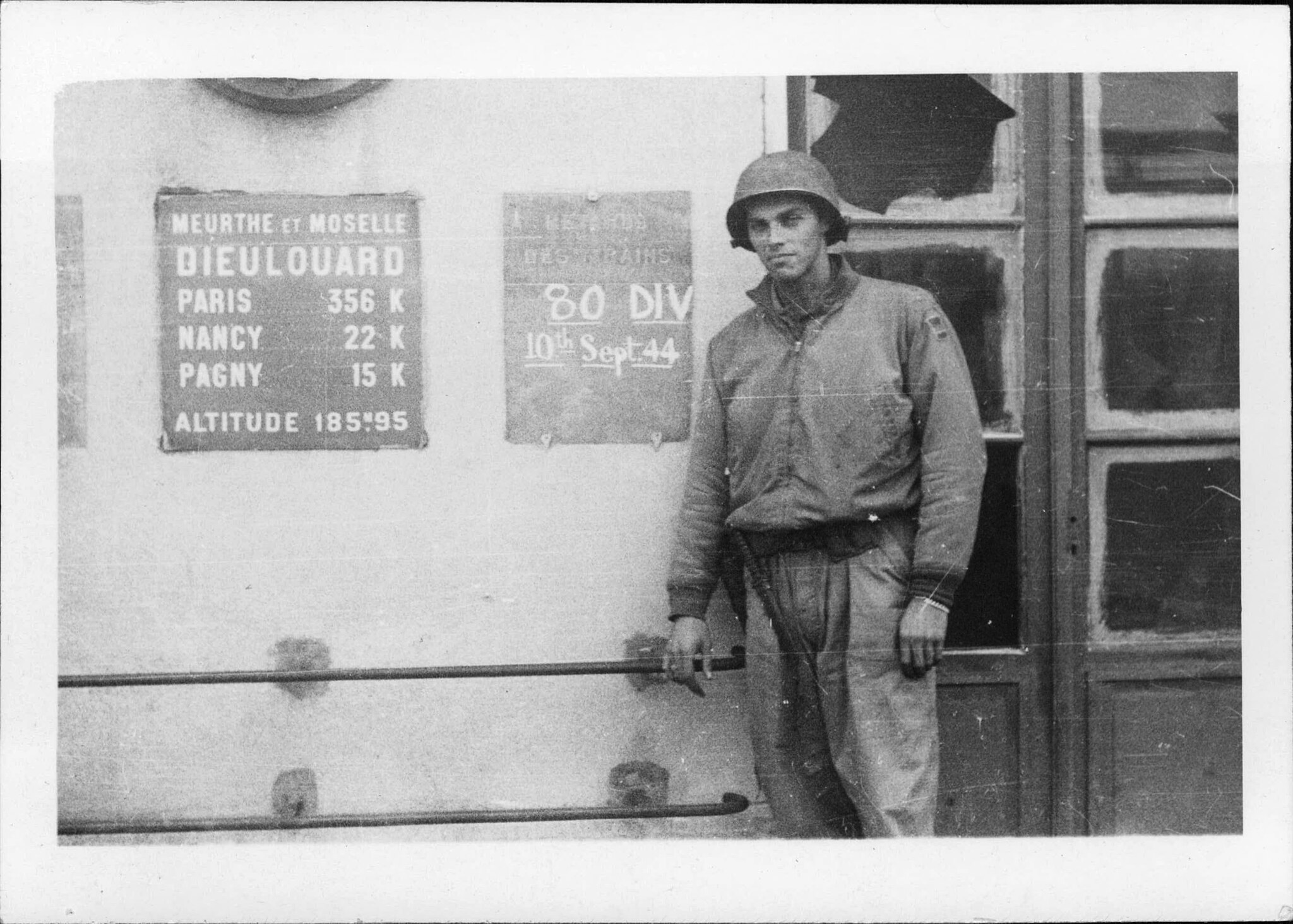

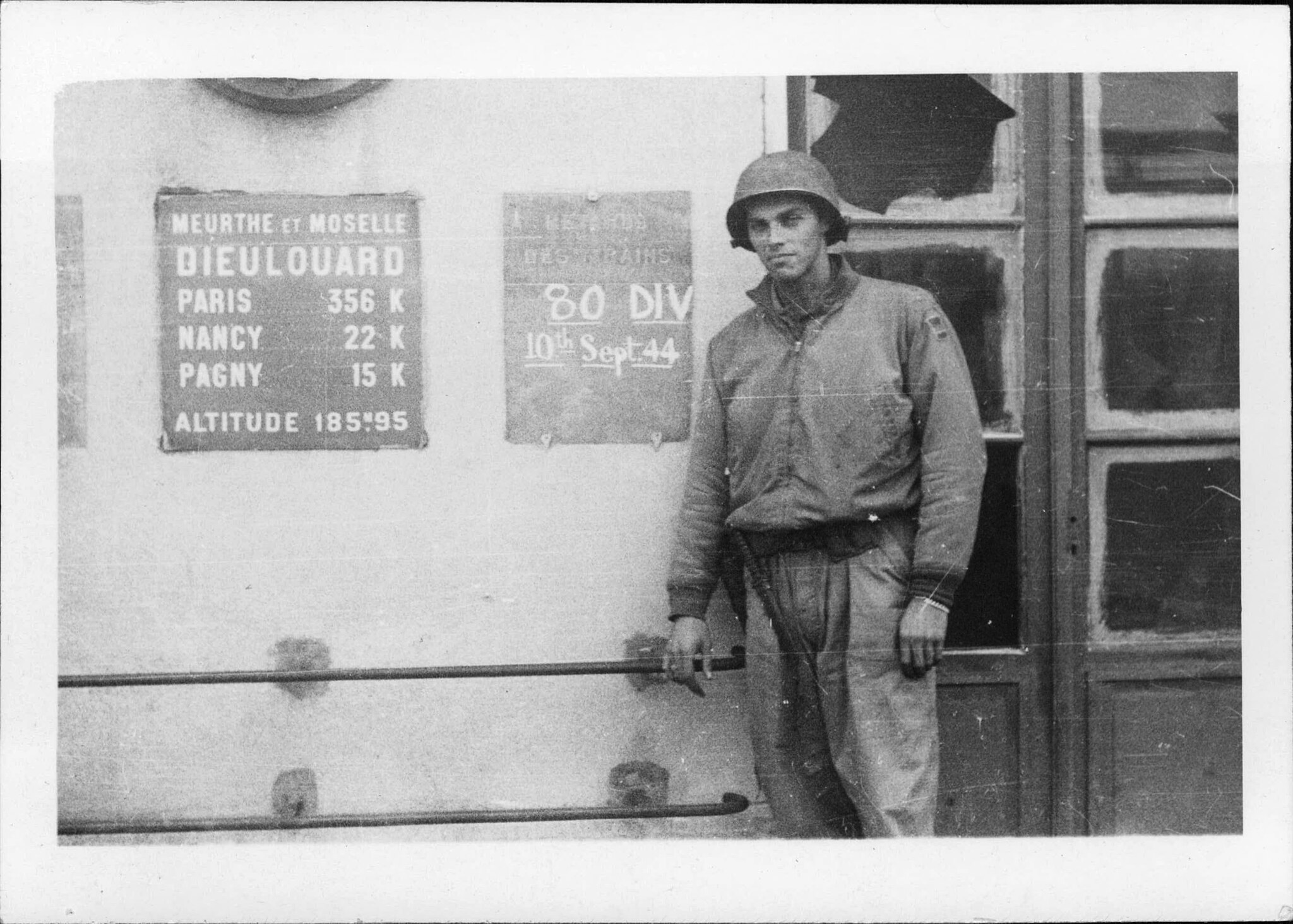

David J Hindlemann was 26 when he enlisted in the army at Ft. Logan, Colorado on November 14, 1942. He was sent to Camp Adair, Oregon for his basic training. From there he went to Ft Sill, Oklahoma for Officer Candidate School. He became a 2nd Lieutenant September 2, 1943. At Ft. Sill, he became…

Arrayed south of the Seille River in October and early November, 1944, the 80th had time to identify targets and sight artillery prior to the battle for Luxemburg and the Battle of the Bulge. Major General McBride noted that new methods of identifying targets over the horizon with the use of reconnaissance planes and oblique…

An Insight into General Searby and Dave’s Account of The Battle of Mousson Hill. (Oral history August 2006) Crossing France as part of the 3rd Army under General Patton: …the General [Searby] used to go on reconnaissance so we’d get in the Jeep – he had to see the lay of the land so he…

We helped Dave as he tried, without luck, to recover his service records. All we knew about his military service was what he told us. No recorded oral history was taken until August 2006, a few weeks before he died. Jo and I were in Denver visiting him and we asked him to give us…

The Challenge of Research Working in our Prescott, Arizona home on a cold January day in 2010, some of the photos and documents fell from the brittle folders. Captain David Jay Hindlemann had carefully placed them in a satchel after World War II. Luckily, many photos had dates or captions written on them. Others cried…